It seems like we can’t make it more than a month without hearing about some type of major storm event that causes havoc in the South and devastation across the Northeast. Most recently was the “bomb cyclone” that brought with it subzero temperatures and massive flooding — not to mention its crippling effect on all forms of travel.

My first platoon at SEAL Team 2 was considered a “winter warfare” platoon because we were going to be deployed overseas during the winter months. This meant we added an additional six months of pre-deployment training to prepare for operating in frigid and potentially unforgiving environments.

First stop was Alaska, where we learned that the only way to work in these extreme environments was to live in them. This meant spending a lot of time outside. We would get dropped off on a Monday morning and told we would be picked up (sometimes 50 miles away) the following Friday.

We learned quickly it was ALL about energy conservation and equipment economy — the lighter, the better. Some guys went as far as cutting their toothbrush handle in half. Since water is heavy, we relied on the use of mini-stoves (white gas) to melt snow. Hydration is just as important (if not more so) in extremely cold environments, so this was a major priority.

On Thin Ice

Today, I want to talk about a particularly dangerous cold weather scenario that frequently occurs in early winter or during the spring thaw when ice-covered lakes, rivers and ponds aren’t as safe as they appear. This can also happen with extreme temperature fluctuations. (For example, last week it was in the single digits on the East Coast. Today, the temperature is nearing 60 degrees at our office in Baltimore.)

Ice that isn’t thick enough won’t hold a person’s weight. Then the next thing you know, you’ve fallen through and plunged into the icy water below.

I know right now many of the lakes in the Midwest and Northeast are frozen over. Please use caution if you decide to go out on the ice and NEVER go alone! If you do happen to fall in, here’s what you should do to make it out alive:

1. Do everything you can to keep your head above the water. Your only goal for the next minute is to not drown.

Once a person is immersed in freezing water, the body experiences a phenomenon known as cold shock response. This usually results in rapid, uncontrolled breathing (hyperventilation) and causes loss of coordination, posing a risk of drowning due to impaired swimming ability. In extreme cases, the shock from sudden immersion in cold water can lead to cardiac arrest.

Fortunately, cold shock response only lasts a minute or two. Your only job at this point is to keep from drowning. Once this initial condition has passed, it’s time to try to get out of the water.

2. Get out of the water as quickly as possible. Water takes heat from your body 25 times faster than air of the same temperature.

Head to the edge of where you initially fell through the ice. This is your escape route. Don’t panic — you should have anywhere from three–eight minutes in which you will have enough strength to get out.

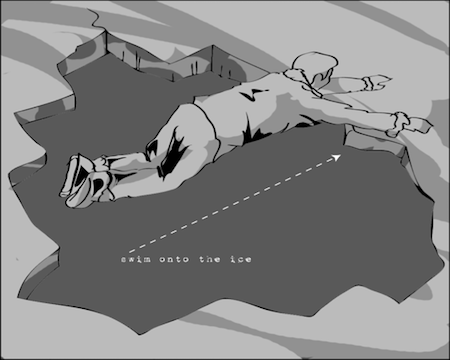

Since you generally won’t be able to lift yourself up and out, you want to instead “swim” out by getting your body as horizontal as possible. Lean forward onto the ice and kick your feet as you would if you were swimming. As you do so, use your arms and elbows to push and pull yourself out of the hole.

An alternative method is to try to roll out and away from the hole. Do this by floating on your back and hooking your strongest arm over the ice. Bring your leg on the same side up over the edge and begin rolling up onto the ice. Make a throwing motion with the opposite arm in the direction of the roll while bringing the opposite leg up as the roll commences.

3. Whichever method you use to get out of the water, DON’T stand up immediately.

Assume the ice is still too thin to support your weight and roll toward the nearest shore. Once you feel that you are on more solid ice, you can get to your hands and knees and crawl until eventually you can get on your feet and off the ice.

Don’t Just Stand There

Let’s say you have just witnessed someone fall through the ice. This is a good time to remember one of the first things you should do in any emergency: Size up the scene. Identify possible hazards and decide whether it is safe to get closer or stay at your location. If you go running out there immediately, you will probably be swimming also.

Then go through the following four steps:

- Take the time to send someone for help or make a call on your cellphone before trying to help the victim.

- Try to talk them out by describing one of the methods above.

- Find something you can throw to them like a rope. Tie a loop in the end you throw to them. They may not be able to maintain a grip on the rope, but they can hook their arm through the loop.

- If nothing is available to throw, find a tree branch, pole or — if you’re near a residential area — ladder.

Back on Dry Land

Once out, the next priority should be removing wet clothes and slowly warming up again. Watch for signs of hypothermia or frostbite and be sure to seek medical care if you experience any complications. However, if you keep the above in mind, you should make it back to dry land with nothing but a good story.

As “new meat” (first platoon at SEAL), there were several rites of passage we had to go through, including something that is commonly referred to as the Polar Bear Club. Simply put, we had to chop a hole in the ice and — with nothing on but our birthday suit — hop in for 10 minutes. I made it, but let’s just say it took a while for some things to start working again once the 10 minutes were over.

Be a survivor… not a statistic,

Cade Courtley