Dr. William C. Padgett is a retired optometrist who has been trying to bring an elderly care facility to Beaufort County, North Carolina, for over a decade.

“Our senior citizens,” he laments, “are finding that it is difficult and in many cases impossible to find an appropriate long-term care facility locally.” Though he has received several commitments from premiere assisted living companies to open facilities in the county, he cannot procure the Certificate of Need (CON) permit necessary to break ground.

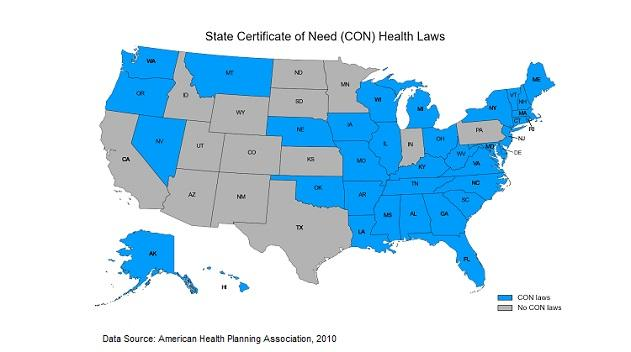

Thirty-six states and the District of Columbia require health care providers to obtain CON permits from their state health-planning agencies before they can offer or expand services. As the name suggests, a CON will only be issued if the agency finds that a genuine need for the service exists in a given community. Sadly, need is not determined by the market, but by politicians beholden to special interests that fear competition.

Though they might sound like something out of Cuba, or the pages of Atlas Shrugged, CONs have a long history in the land of the free.

For the most part, state CON laws grew out of the 1974 National Health Planning Resources and Development Act, which — in a misguided attribution of spiraling health care costs to a “maldistribution” of health care resources — required states to set up health-planning agencies to control future health care expansion based on need.

Twelve years later, in 1986, the federal law was unceremoniously repealed for the simple reason that it had failed in what it intended to do — reduce health care costs. Fourteen states subsequently repealed their CON laws, either because they agreed with the federal analysis that CON didn’t work or because they lost federal funding with the repeal. On the other hand, 36 states chose to double down on their CON laws under the curious premise that too much supply drives up cost.

Essentially, CON backers believe the socialist tenet that the building of potentially wasteful excess supply should be forbidden because it is inefficient and could raise the costs for existing users. According to this theory, economic activity like movie theater expansion should be limited to community need to prevent existing moviegoers from being overcharged should the new seats sit empty.

Barriers to Entry Increase Price

Needless to say, this theory has been thoroughly discredited. Barriers to entry like CONs increase price. As economist Roy Cordato put it:

“There is possibly no proposition in economics that is more accepted than the idea that if you want to reduce the cost of something, you foster an environment that encourages open competition and entrepreneurship and discourages monopoly.”

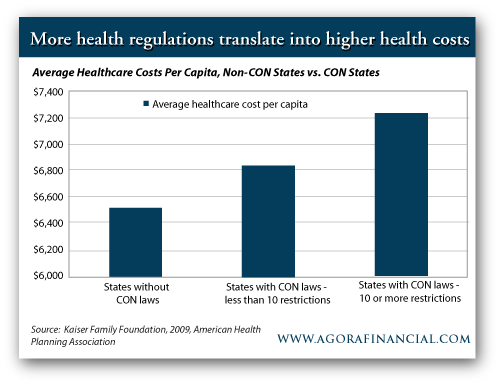

This reality is illustrated by the data, which show that CON laws not only fail to control health care costs but also that they may contribute to increasing them. health care costs are 11% greater in CON states than in non-CON states, $7,230 per capita in the former compared to $6,526 in the latter (see tables below).

Average health care Costs Per Capita: CON States vs. Non-CON States

Further, the data show that states with more services subject to CON approval have higher average health care costs than those with fewer services subject to approval. The severity of states’ CON requirements varies widely, from Vermont, which requires CONs for 30 services, to Ohio, which requires CONs for only one service — the introduction of additional long-term care beds. States requiring CONs on 10 or more services have average per capita health care costs of $7,396, 8% higher than the $6,837 average for states requiring a CON for fewer than 10 services (see chart below).

Academic research backs up this analysis. One high-profile Duke University study in the Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law claimed that CON laws lead to higher, not lower, health care costs: CON laws caused a 2% reduction in bed supply and “higher costs per day and per admission, along with higher hospital profits.” An earlier study in the Journal of Regulatory Economics found that CON laws were responsible for a 13.6% increase in per capita health care costs. Scholars conclude that there is a “remarkable evaluative consensus” that CONs don’t work.

Even the government, never quick to denounce its own policies, has called for CON abolishment. According to a 2004 Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Department of Justice (DOJ) joint report:

“The Agencies’ experience and expertise has taught us that Certificate-of-Need laws impede the efficient performance of health care markets. By their very nature, CON laws create barriers to entry and expansion to the detriment of health care competition and consumers. They undercut consumer choice, stifle innovation, and weaken markets’ ability to contain health care costs. Together, we support the repeal of such laws, as well as steps that reduce their scope.”

Dialysis users in Washington state know firsthand how CONs impact price. In response to rising rates of Type 2 diabetes, Washington’s health care providers sought several years ago to open new dialysis centers and expand existing ones. Their requests for CONs were denied because they did not meet the state planning board’s need requirement. Palmer Pollock, an administrator at Northwest Kidney Centers, says that as a result of this decision, dialysis prices in Washington state have skyrocketed: “Private carriers used to pay $200 or $300 per treatment . . . now it’s more than $1,000.”

Maintained by Cronyism

So with all this evidence that CONs are harmful, how do they still exist?

One reason is that they find support from a classic “bootleggers and Baptists” coalition. The bootleggers and Baptists story has its origins in the days of prohibition, when two very powerful yet very different groups, the bootleggers and the Baptists, unwittingly teamed up to keep alcohol illegal. The Baptists favored prohibition for moral reasons while the bootleggers favored it for profiteering ones. The groups’ joint support for the alcohol ban helped keep prohibition alive.

Many of today’s policies are similarly backed by unexpected coalitions, with CON laws being prime examples. They are kept alive by a coalition of misguided moralists supportive of any well-intended policy purporting to keep health care costs down and by opportunistic cronies looking to use State power to shut out new competitors who might eat into their profits.

State health planning boards are often directly or indirectly under the influence of existing health care establishments looking to regulate potential new entrants who may negatively impact their bottom lines. The American Hospital Association was an early supporter of CON laws, engaging in a nationwide lobbying effort to pass them at the state level and drafting a model state law in 1972. The FTC and DOJ report reveals:

“Existing competitors have exploited the CON process to thwart or delay new competition to protect their own supra-competitive revenues. Such behavior, commonly called ‘rent seeking,’ is a well-recognized consequence of certain regulatory interventions in the market. . . . During our hearings, we gathered evidence of the widespread recognition that existing competitors use the CON process to forestall competitors from entering an incumbent’s market.”

In addition to rent-seeking, CON laws also invite good old-fashioned cronyism. Perhaps the most infamous case of this was the sordid 2004 tale of the CON procurement for the building of a new hospital in suburban Chicago. According to the indictment, four parties — an official from the Illinois Health Facilities Planning Board, the contractor of a major construction company, a financier from a major investment bank, and the CEO of the proposed hospital (who was by this time wearing a wire for the FBI) — conspired to operate a classic kickback scheme wherein the hospital would receive a CON on the condition that it be built by the aforementioned construction company.

In return for granting the CON, the planning board member would receive a cut of the $100 million construction contract. Though this act was despicable, it should not be surprising that when people can’t use the price system to achieve their ends, they will resort to graft and cronyism instead.

The United States is in a desperate struggle to control health care costs and improve access. Rather than pinning our hopes on grand plans to overhaul the system, we should first look at where we can make changes on the margin that would move us in the right direction. Abolishing CON laws — a barrier to entry that drives up price, restricts access, and is maintained by cronyism — would be a great place to start.

— Jordan Bruneau

This article originally appeared here on the Foundation for Economics Education website.