The 20th century was an age of big business. And investors did well backing the giant blue chips on their march to glory. But those days are over. In its simplest terms, my thesis is to bet with the small guys.

I think of them as cottage industrials. A cottage industry brings up images of small-scale, local industry. It’s a good metaphor for what I have in mind.

Author William Thorndike sets the scene:

“In American business, there is a deeply ingrained urge to get bigger. Larger companies get more attention in the press; the executives of those companies tend to earn higher salaries and are more likely to be asked to join prestigious boards and clubs. As a result, it is very rare to see a company proactively shrink itself… [Yet] growth, it turns out, often doesn’t correlate with maximizing shareholder value.”

It used to be economies of scale meant you had to get bigger. But there are also diseconomies of scale. Companies can get too big. They can get inflexible. They can saddle themselves with such enormous expenses to support that they no longer can compete effectively in smaller spaces. Yet the returns in those smaller spaces are richer than in the open plains.

Jim Gober, the CEO of Infinity Property & Casualty, told me something fascinating about his business. (Infinity is a small auto insurer.) He said that even with all the advertising dollars spent by the big companies in recent years, consumers are no more likely to switch insurers. As a result, the small guy could compete on price by not spending the money on national advertising. By not having to maintain a national “brand,” he kept his costs lower.

So Infinity has been able to compete successfully with companies 50 times as large in small markets. In fact, Infinity has outperformed them in almost every way for the whole 10 years of its existence as a public company — including the one that really counts: returns to shareholders. The big companies don’t have what it takes to compete with Gober on his own turf. They can’t.

Size, then, can actually be an impediment to good shareholder returns.

Think about what keeps the giants humming. Fat-cat salaries for the brass. Lavish bonuses and stock option plans. Corporate suites with wood furniture and art on the walls. Headquarters in office towers that employ thousands of people. (Doing what? I always wonder as I walk past them in Manhattan.) Glossy annual reports that say nothing. And to top it off, they produce mostly lousy products that people hate. (Does anybody love Microsoft’s products? Try LibreOffice. It does everything Microsoft Office does — for free. It is hard not to love free.)

Where is the shareholder in all this?

Nowhere… The big blue chips are mostly faceless, bureaucratic monstrosities. Like all bureaucracies, they exist to pile food on their own plates. Shareholders are people to keep quiet and out of the way.

A better model is the cottage industrial.

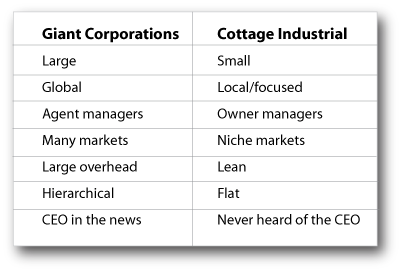

But what is a cottage industrial exactly? The table below stacks up, in general terms, what I think of as “cottage industrial” set against the giant offspring of state corporatism:

Here is another example of a cottage industrial: Contango Oil & Gas.

Ken Peak is the founder and was the CEO and largest shareholder until recently. He was an owner, not an agent. Even at Contango’s height, it was a fraction of the size of large natural gas producers like Chesapeake. But Contango focused on creating value per share. It had eight employees and just 11 wells. Its biggest expense was taxes.

Contango was always among the lowest-cost producers of natural gas in North America. As an investment, investors are up over 2,000% since inception in 1999 — trouncing the Dow’s paltry 26% over the same period. (That’s the Dow Jones industrial average, made up of the giants of American business.) Contango’s investors have been up as much as 4,000% before natural gas prices collapsed.

Contango, as with Infinity above, is a model of the kind of business I’m talking about owning.

All is to say there is an alternative to having to shack up with the swollen GEs and AT&Ts of the world. Your returns will be greater, and instead of backing overpaid CEOs, expense accounts, overhead and bureaucracies… you’ll own shops where people are intrinsically motivated to do well because they own a piece of their work. You’ll own something you can grasp on a human scale.

Our entire portfolio is made up of companies I consider cottage industrials. They are small players in their industries. They focus on local niche markets. They are lean. And they are run by owners — not hired agents.

But there is more to this story…

***The Cottage Industrial Revolution

The above is a simple enough idea. In some ways, the above has always been true. What makes it timely for today?

I have to backtrack a bit and tell you about the darker side to gigantism in Corporate America. It is the history no one talks about. The history that tells you how much the state and big business are partners in crime.

For example, one of the biggest misconceptions about FDR’s New Deal is that it was somehow revolutionary and anti-business. Actually, it was the culmination of a trend that began much earlier. And business welcomed it.

The great Murray Rothbard summed up government intervention this way:

“The intervention by the federal government was designed, not to curb big business monopoly for the sake of the public weal, but to create monopolies that big business… had not been able to establish amidst the competitive gales of the free market.”

He cites the work of Gabriel Kolko, who showed how the vast structure of regulations we take for granted was conceived by — and championed by — big businessmen.

If you apply this kind of thinking to today’s giants, it is not hard to see how government policy enabled them to achieve their great girth:

- What is Boeing if not for the military-industrial complex and the huge sums of tax money dumped into building civil aviation?

- What is JP Morgan without the helping hand of the Federal Reserve Bank?

- What is Wal-Mart without the U.S. taxpayer laying out the enormous capital required to build out the nation’s interstate highways and railroads to carry its cheap junk? Without zoning laws and licensing fees that stifle competition from the small shopkeeper?

- What is Microsoft or Pfizer without the state-granted privilege afforded by copyright and patents?

To answer my own questions: At a minimum, these firms are much smaller without the taxpayer subsidy. State privilege was a crutch that made them the giants they are today.

Today, the state weakens as its finances soften. The state can’t keep up with the roads. Intellectual property is harder to defend in an Internet age. New technologies enable all kinds of small-scale producers to compete effectively with giants.

At the very least, this thesis means lower returns for the old giants. The behemoths that prospered in the old world are ill fitted for the new world that awaits them. In impact, this new world could well be akin to another industrial revolution. Hence, the cottage industrial revolution.

I haven’t fleshed all of this out fully, but I’d be interested to hear your thoughts. Am I crazy? Or do you too see how small, or locally based, owner-managed businesses are turning the tables on the giants — like Infinity?

I admit to a bias.

When I travel, I aim to stay at locally owned hotels. When I seek out good restaurants, I go for the local haunts, not the chains. I prefer locally grown produce over gas-ripened tomatoes shipped from 1,000 miles away. (We have a milkman, for crying out loud!) Local is often better, in more ways than one. But mine is also a personal revolt against sameness and mass-produced crap. This carries over to my investing style, too, as I much prefer a smaller company that I can get my hands around to trying to figure out, say, GE.

Sincerely,

Chris Mayer