Over this past Memorial Day, I sat down with a couple buddies who had just got back from serving overseas. I told them how only a few weeks ago I was shaking hands with Marcus Luttrell of Lone Survivor fame.

Marcus was the sole survivor in an event that ended in the largest loss of life in Navy Seal history. I knew the story, but I was shocked by what he said when I met him…

He stood in front of a room full of people, where I was at the front, and he said:

“I’m not a war hero. Please don’t call me that.”

“I’m a gun fighter. That’s all.”

Is he a hero? Or none at all? Or just a humble one? That all depends on your perspective. But naturally, as I told this story to my military friends, my Memorial Day conversations went from war and all the individual soldiers whose deeds are unknown, unrecognized or little understood… to another class of warriors — the kind I spend most my time studying, because they do at least as much to keep us all alive.

They aren’t dressed in uniforms — at least, not most the time — but their work, during their lives and after they die, can absolutely make or breaks nations. Even superpowers.

Yet most people have no idea who they are. So let’s test your knowledge…

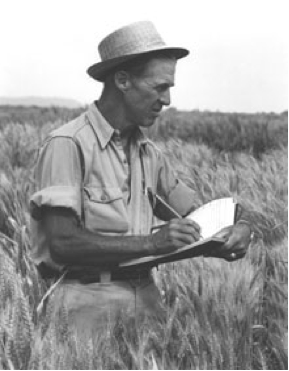

Do you know who this man is?

According to some estimates, he’s saved one billion lives. (Remember, there are 7 billion people living on the planet now).

His name is Norman Borlaug, and by developing new crop varieties and growing methods — basically using biology to influence seeds — he has probably saved more lives than any man living.

The technology he finely tuned was spread to other parts of the world where people go hungry. In short, he started the Green Revolution, and has fed more people than any other human being in history.

If you ever wondered at some point why India and China no longer have massive famines, it’s because Norman Borlaug taught them how to grow grains in a more efficient way. Now, instead of having starving people, India and China are exporting grains.

But here’s the funny thing…

Borlaug started his research in Mexico.

Yet there are no monuments of Borlaug in Mexico. There are in China and India.

That’s because Mexico rejected Borlaug’s vision. They didn’t adopt his technology. They ignored it. And today, Mexico remains one of the largest importers of grains on the planet.

I learned a lot about the Norman Borlaug story through Juan Enriquez.

Among other things, Juan was CEO of Mexico City’s Urban Development Corporation, where he was responsible for transforming part of a major city into a flourishing modern day metropolis.

“The Institute that this guy ran,” says Juan of Norman Borlaug, “has now moved to India.”

“That is the difference between adopting technologies and discussing technologies.

“It’s not just that this guy fed a huge amount of people in the world. It’s that this is the net effect in terms of what technology does across the world.”

“Innovation is this very strange seed,” he says. “And it plants itself in different climates and different places. And over the past century… it sprouted in the United States.”

As a prime example, Juan emphasizes, “The area around MIT is equal to about the 13th largest economy in the planet.” We’ll pause a moment to let you think about that.

If we take that idea seriously, then Cambridge Massachusetts, through the knowledge output of its universities and the economic output of its companies…

…generates more wealth than South Africa, Ireland and Switzerland, combined.

How is this one zip code in the U.S. outperforming multiple developed countries?

In these U.S. zip codes, these clusters of technology and innovation, the government helps an abundance of small ventures, and then gets out of the way.

Contrast that with a place like Detroit, where there’s not an abundance of small and innovative companies… but a small number of big corporations, like GM. When a company like GM goes belly-up… everyone in the area feels the pain, and they take much longer to re-adapt.

According to Juan, “this road is splitting quickly” when it comes to super-zip codes and poverty-stricken areas.

In the age of globalization, scientists, technologists, engineers and other “knowledge economy” leaders are not limited by geography. If the government stops giving them a grant, they pick up and move somewhere else. Like Norman Borlaug.

You can see this going as far back as WWII. German rocket scientists didn’t want to come to the U.S. They wanted to stay in Germany. But America had money, and we made it worth their while.

Much of “the dividing road” is cultural. After Sputnik was launched, mothers wanted their kids to be scientists and engineers. And now there’s a divide, even a fear, of science and technology — as if it has to threaten our value system.

Take an example of more recent times. When the Bush Administration halted funding for stem cell research, the scientists involved moved wholesale to China. Fortunately, there were no limitations on private development, and states like California chipped in with new money for R&D. That was enough to sustain a critical mass for stem cell research.

But probably some of the best medical research that’s done in the world is at Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which housed 550 some scientists at the time. After Bush halted funding for stem cell research, almost 100 went straight to China.

That same scenario could happen in any other field of science and technology. If that happens, the evaporation of wealth in America would be as devastating as it would be unnecessary.

– Josh Grasmick

This article originally appeared here.