I just spoke to a friend, Skinner Layne, who is from Arkansas, but now lives in Santiago, Chile. He emigrated there and is now heading a startup enterprise that is showing great promise. It is called Exosphere. I asked him about the backstory to the company. It turns out that he moved in 2008, six months before the U.S. real estate markets blew up. He left to escape the worst of it.

How did he know that the downturn was coming? His answer came quickly: “The yield curve inverted.”

Fascinating.

I was just reading about this very indicator in Mark Skousen’s new book, A Viennese Waltz Down Wall Street. Here, Skousen, investor and economist, explains how the teachings of the Austrian School provide some excellent rules of thumb that allow us to anticipate, and act on, the big turns in the business cycle.

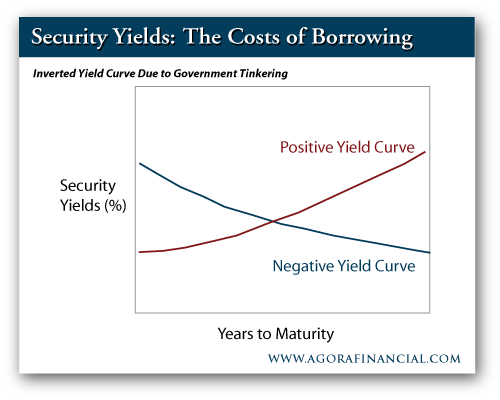

In the Austrian view tracing back a century ago, interest rates indicate the preference for goods sooner, rather than later. If you don’t have the money to get the stuff, you borrow for some period of time. Borrowers pay a higher rate if their payback term is longer. That’s because the risk is higher — who knows what’s going to happen in 30 years? — and lenders expect a higher payoff to wait longer for their money. So naturally, the yield curve should show lower overnight rates than five-year, 10-year, or 30-year rates. That’s why the normal yield curve is positive — that is, upward sloping to the right.

What does it mean for the yield curve to be negative? It’s a bit like water running uphill. You can be pretty sure that there is some seismic shift going on. Usually, it means a Fed tightening. Or it could mean that investors are expecting bankruptcies in the future. It is highly predictive of a coming recession.

When it happens, you can also be sure that hordes of television pundits and economists will emerge to say that there is nothing unusual here. It is a perfectly normal thing, and it’s even healthy — certainly nothing to be alarmed about.

My friend Skinner knew better. How? He had been reading the work of F.A. Hayek and Ludwig von Mises for years. He knew that there are certain constants in economic forces that do not change, no matter what government does. In fact, government and central bank attempts to manipulate the market can have exactly the opposite effect of the advertised results.

TV pundits are quick to agree with everything the Fed does. To spot the policy errors requires special knowledge that comes from reading sound economics.

That doesn’t mean that once you learn economics, you can predict the exact timing of events. In fact, this is also one of the observations of the Austrian School: There are no predictable quantitative relationships in the world of human action. This too differs from the mainstream view, which is forever seeking the magic formula to predict price movements.

I like the way Skousen describes financial markets. He says that prices in markets are like a dance. There are patterns and habits at work. But there are also surprises and improvisations going on. That’s part of the spirit of dance too. But the crucial thing here is that it takes two people to coordinate their moves in a dance, just as in markets, it takes buyers and sellers to make a price. Financial markets bring people together to their mutual benefit.

Nice image, isn’t it? It’s one that he elaborates on at length. In the course of his argument, he criticizes other points of view that don’t account for human decision-making and don’t account for the parameters of those decisions as set by economic reality. For example, just as dancers can’t start flying, markets can’t sustain parabolic price increases in one sector forever, even with Fed intervention.

Why did Skinner choose Chile as his home? Well, he knew it to be the most pro-enterprise country in Latin America, at least so far as he could tell. His reading in the Austrian tradition helped him see why this is important.

And he likes Latin America because it is the new world and doesn’t have economies bogged down by bad habits and massive welfare and regulatory bureaucracies. There is far less sludge in the system to harm economic growth. For this reason, he is very bullish on the whole region — and bearish on the U.S. and Europe.

This too reminds me of something else explored in the Skousen book. He discusses how institutions affect economic growth and can help people make better predictions about coming economic booms. A regime that is friendly to free enterprise might lower taxes or cut regulations. Even a little bit helps. Economies are like sponges for this stuff. Just a bit of encouragement — or, more precisely, just a bit of relaxation of the fetters — can spark huge economic booms.

This is why Skousen strongly suggests following the politics of a country to understand its economic future. He goes so far as to slightly scold fellow Austrians for holding a permanent bearish view on economies. He says that this point of view causes investors to miss economic booms such as, say, those in the 1980s and 2000s. And he is right to this extent: If your goal is to play the markets, it makes sense to be able to discern their upside, as well as their downside.

Monetary policy figures in here substantially. As Skousen says, an economy without a huge debt overhang that is emerging from rough economic times can find itself on an upswing if the Fed is pumping money at a rapid pace. Under this rule, you might have bought stocks in 2009. The problem is that this approach to economic policy cannot last. It creates new problems that cry out for correction. The tricky thing is to be able to spot the turning points.

What do Austrian economics imply about today’s precarious situation? Well, the Fed is making loud noises about pulling back its stimulus program. If the drug of new money is cut off, we could see short-term rates rise and blow up the balance sheets of many businesses, not to mention governments.

The beauty of the Austrian School is, fundamentally, this: It sees economics as an extension of human choice. There is nothing mechanical and predictable about it. But there are certain patterns that emerge just from the logic of human action itself. Skousen’s purpose here is to elucidate that logic and illustrate it with examples from the business pages. The results are interesting: You can gain insight into both worlds. In this book, the rubber of finance truly does meet the road of economics.

I’m intrigued at the confidence with which my friend Skinner took the step to move. Five years later, he has a thriving business and a happy life. He only did it once he had intellectually seceded from mainstream thinking. But just as important, he did it with the aid of solid economic thinking.

Now with Skousen’s book A Viennese Waltz Down Wall Street, anyone can gain access to that knowledge. A selection like this makes a mighty contribution.

Sincerely,

Jeffrey Tucker